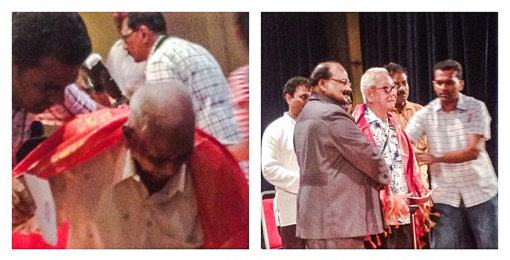

Twelve years of hard work clearly reflected when Dr Kurunjivendam of University of Pondicherry, India held a screening for his documentary titled “Nadodigal” at Dewan Tan Sri Soma, Kuala Lumpur, recently.

The documentary, which is the only one shot in Tamil, showed vivid images of Malayan Tamil indentured labourers through the recollection of nine survivors of the ordeal.

Throughout the documentary, the audience were choked on tears while listening to the recollection of the survivors.

“Throughout the night you could hear the Tamils crying out loud for God “Samy!..Samy!” (God!..God!) and in the next morning, they all gone,” remembered Loke, on high death toll in labour camps due to cholera, malaria and dysenteries.

Loke Wing Yew, a Malaysian Chinese, is one of the survivor who remembered the agony and death pain that the forced Tamil labourers went through in the detention camps.

Another survivor, Mohamad Hanifa shared his experience, that they had nothing to wear.

“Sometimes we will be wearing “gunny” sacks..that was all,” said Hanifa.

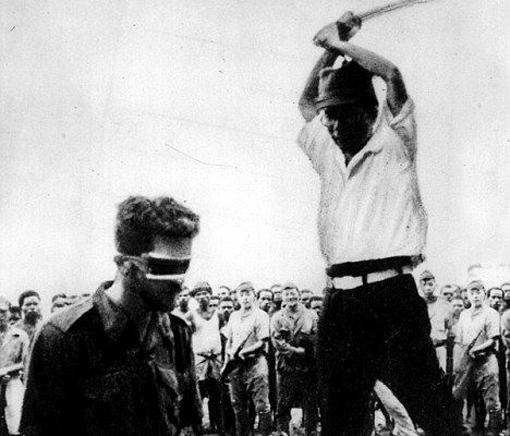

The screening was a very emotional presentation where, some of the audiences were weeping throughout the film. The atrocities committed by the Japanese Army during World War 2 were unimaginable and reminds the ugly sides of wars.

The 415 km railway started its construction in June 1942 and took 15 months to complete. At the end of the completion, around 80,000 Asian labourers or known as “Romusha” lost their lives.

“When British Army was defeated and Singapore fell to the Japanese, the Japanese had around 60,000 British soldiers in their captive. With these prisoners of war, they deployed another 200,000 Asian labourers to swell up the workforce to build the railway,” said Dr. David Bogget, a scholar from Kyoto Seika University, Japan.

“Many of the conscripted labourers were the Tamil indentured labourers from estates in Malaya,” added David, who also had presented many international papers of the Siam-Burma Death Railways.

After the war ended many of the labourers were brought back to Malaya by the British army but many too did not made their way back. They were left in Burma and Thailand. One of them is Paalpaandi.

Paalpaandi, who is now in his late 90s and living in Moulmein in Myanmar, were not conscripted to build the railway road. Instead, was taken to build a land road along coastal way connecting Thailand to Moulmein in Myanmar.

“We were brought from Malaya to clear the jungle to build the road. I did not have the change to go back,” spoke Paalpaandi in shaky tone.

According to a Malaysian Tamil writer, Rengasamy, who have done many interviews of survivors of the death railway, told that many of us are not aware there were also two more deadly projects undertook by Japanese Army along with Siam-Burma railway. They are the land road construction along the coastal area of Thailand-Burma and Kra Isthmus Railway.

“The land road along the coastal area of Thailand and Burma is known as “Marana Mansadakku” (death land road). The death railway tragedy was known well to the world due to many POWs were employed unlike the coastal road,” said Rengasamy.

After war ended the miserable plight of the forced labourers did not end in Siam alone, but continued even when the survivors returned to Malaya.

“When we returned to our families in Malaya, the men were in great shocks to find out their wives are married to somebody else, our parents and siblings dies in the war, families were shattered and nothing else left for us,” said one survivor, Muniandy.

He also added that the Japanese “banana tree” currency which they brought back from Siam lost its value after the war.

“Some of my friends who survived the death railway ordeal in Siam ended their lives in Malaya by committing suicides,” he said.

The effort by Dr.Kurujivendan, who has launched the film in Paris and London, as many of the Siam Burma Death Railway documentary revolved around the POWs, is applaudable.

This is one of the first efforts ever to mark the contribution of the Asian labourers in construction of the death railway.