The Baba and Nyonya community in Penang, especially those of Hokkien descent, epitomise the phrase “something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue,” similar to a Western bridal tradition.

Rooted in the 15th-century arrival of Chinese settlers adopting local customs, their culture blends “something old” with evolving practices represented by “something new.”

Influences borrowed from the indigenous Malay people create a harmonious blend, and the maritime trade roots reflect “something blue,” subtly alluding to British influence.

Cultural fusion of Baba Nyonya

Chinese maritime traders engaged in trade with the Malay Peninsula as early as 618 AD, and these influences continue in the Baba and Nyonya community, also known as Peranakans, found in various regions.

Tian Chua, a former Member of the Parliament who identifies as a Baba from Melaka, stated that the Straits Chinese adopted Malay culture, seeing it as superior and aligning with the region’s historical context.

“They saw the Malay culture as being superior and thought that China was a backward nation.”

The Baba and Nyonya community distanced themselves from certain Chinese practices, such as foot binding, showcasing their adaptive nature and genuine acceptance of local customs.

“At that time, Chinese women, including my grandmother, wanted to escape foot binding. We maintained the Chinese cultural aspects and incorporated aspects of the local community which seemed superior to the ‘backward’ mainlanders and new immigrants, or ‘sinkhek’.

“Baba and Nyonya are essentially Chinese people who embraced the Malayan socio-economic, and later political conditions,” he said.

Syncretic identity and Pinang Peranakan Mansion

The community retained Chinese folk religion, adapting it to local folklore. For example, the ‘Datuk Kong,’ a protective deity, is depicted as a Malay Muslim in their shrines, showcasing the syncretic nature of their identity.

Shrines and altars dedicated to the ‘Datuk Kong’ have statues that bear resemblance to a Malay man who dons a ‘songkok’, the Malay headgear.”

This cultural blending reflects the syncretic nature of the Baba and Nyonya identity, as they embraced aspects of both Chinese and Malay cultures to form a unique and harmonious way of life.

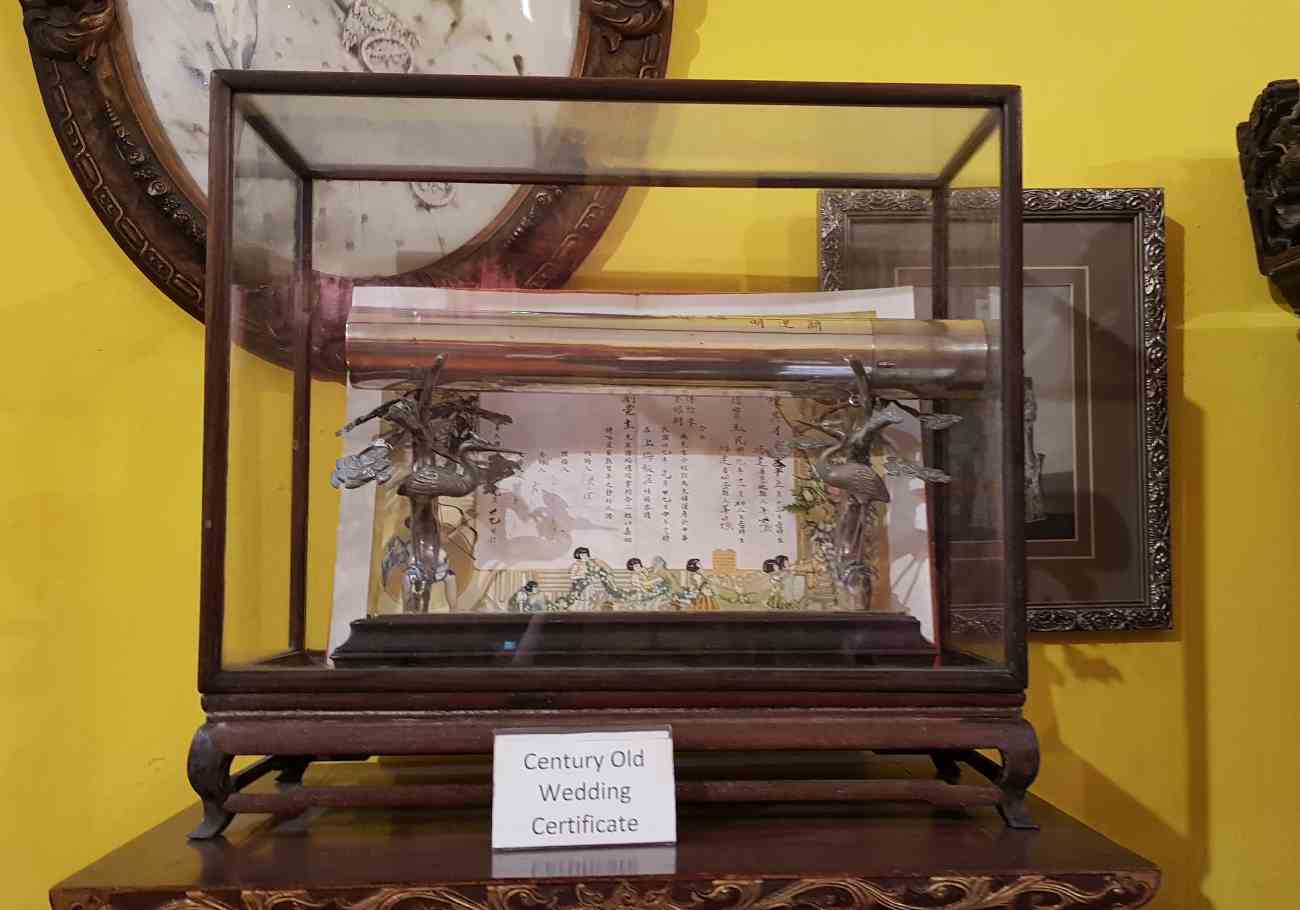

The Pinang Peranakan Mansion on Church Street provides insight into the lives of wealthy families in late 19th-century Penang. The mansion exhibits beautifully designed rooms with Baba and Nyonya artefacts, showcasing both Western and Chinese influences, including Victorian-era items.

“There are both Western and Chinese influences alongside here. Besides the beautifully designed furniture, there are Eglomise, which are reverse-painted mirrors, and bell jars that were popular in the Victorian era.

Tulips, which were prized as much as gold during that time were also appreciated, as were marble statues made of Carrara marble, the same marble that Michelangelo used for his statues,” explained Dato’ Lilian Tong, who is the president of the Persatuan Peranakan Baba Nyonya Pulau Pinang and the deputy president of the State Chinese (Penang) Association.

Baba Nyonya culture wanes, leaving imprints

Lilian also noted the acculturation process, where Baba Nyonya elements became synonymous with broader Penang Chinese culture. Despite the fading distinctiveness, core values like prioritising family and education remain unchanged.

“Eventually, many Baba and Nyonya opted to register their children as Chinese in their birth certificates,” explained the larger-than-life yet elegant Nyonya.

“We were mostly English-educated and communicated with a mix of Hokkien, English and Malay at home. Due to this, we were also sometimes called ‘bananas’, yellow on the outside and white on the inside,” she rued.

“We are also slightly different from the Baba and Nyonya in Melaka in that sense. There are families in Melaka who spoke mainly in Malay.”

The process of acculturation has played a significant role in the gradual disappearance of the distinct Baba Nyonya culture, blending it seamlessly into the identity of Penang’s Chinese community today.

The once-distinctive elements of Baba Nyonya traditions, including the language spoken, “Penang Hokkien,” and the enjoyment of culinary delights such as “chap chai,” “nasi lemak,” “otak-otak,” and sweet treats like “kuih kapit,” “kuih bakul,” and “kuih bangkek,” have seamlessly merged with the broader Penang Chinese culture.

As evidenced by the Malay names used, these delectable dishes subtly hint at the unmistakable roots of the Baba and Nyonya heritage.

Preserving legacy while embracing change

Aunty Pat, an 81-year-old Nyonya, emphasised the need for evolution while preserving core values. She highlighted the importance of education, and many Baba and Nyonya individuals work in the public sector.

Aunty Pat, a Convent Pulau Tikus graduate, shared insights into traditional attire like the “kebaya” and “sarong,” emphasising the unique craftsmanship in Penang.

“The Baba and Nyonya always put family first, then our neighbours and community come next. That is why education is always a priority, and many of us work in the public sector,” she said. Aunty Pat was given the name “Patricia” by the sister of the Convent Pulau Tikus.

“I was the first batch at CPT, both for the primary and secondary school and graduated with Senior Cambridge in 1959,” she recalled beamingly.

Although she now wears her hair short and no longer wears a “sanguih”, she still maintains the kebaya and “muar” or sarong as her daily attire. “Sanguih” is from the Malay word “sangul” as is the word “sarong”.

In Penang, many Malay words are used, but with the many last letters being replaced by the letter “i” or “ih”. Hence “mari” becomes “mai”, “aduh” becomes “adui”, and “betul” becomes “betui”.

“Penang ‘kebaya’ has the perfect cut or ‘potong coat’ that follows the curve of the body,” claimed Aunty Pat.

“To know if a ‘kebaya’ is made in Penang, just look at the underside of the cloth to see if both sides of the embroidered ‘kerawang’ which is the lacework, look exactly the same.”

On a lighter note, Aunty Pat humorously shared that the traditional Nyonya camisole, typically crafted from cotton and hand-stitched by Nyonya artisans, featured two large front pockets.

These served various purposes, including carrying small objects like “tangkai” (amulets) and, more amusingly, providing coverage since brassieres were not worn during that era.

In Penang, where the Baba and Nyonya heritage fades into the contemporary Chinese identity, the essence of their rich history remains, echoing through traditions, attire, and of those like Aunty Pat, who continue to carry the legacy forward.